As the old pilot’s poem said so eloquently, Henry Sanford “Sandy” McMurray has “gone west”, or in other words, after 99 and 1/2 years on February 13, 2021 Sandy filed his last flight plan.

Sandy was born July 14, 1921 in San Leandro, California to Welborn and Harriett McMurray. His love of flying began when he soloed at the age of 19. Flying eventually became his passion, profession, avocation, and except for his family, the core of his life.

In November 1941, one month before the United States’ participation in World War II, Sandy enlisted in the US Army Air Corps. With two years at San Jose State University behind him and at 20 years old, he had the prerequisites to become a US Army Air Corps officer and did so when on July 3, 1942 he became a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army Air Corp Reserves at the age of 20.

Following flight school training at Ellington Field in Texas he was assigned to the Eighth Air Force, 305th Bombardment Group, 366th Bombardment Squadron, piloting B-17s over Nazi controlled Europe. Sandy was stationed in Chelveston, England, the backdrop for the movie 12 O’clock High though they changed the name in the movie. On Sandy’s second mission, January 27, 1943, the 305th bombed the Nazis navy yards at Wilhelmshaven when heavy bombers of Eighth AF made their first penetration into Germany. Through mid-1943, the group attacked strategic targets such as submarine pens, docks, harbors, shipyards, motor works, and marshalling yards in France, Germany, and the Low Countries. On Sandy’s 11th mission, April 4,1943, the 305th BG received the Presidential (formerly the Distinguished) Unit Citation for a mission to an industrial target in Paris that was “bombed with precision in spite of pressing enemy fighter attacks and heavy flak.”

At the age of 21 Sandy was captaining a Flying Fortress, with a crew of 10 men, into historically the worst air combat the US has ever experienced. The B-17 was stable, forgiving of crew mistakes, well built, could take an unbelievable amount of battle damage, and still bring its crew home. At their first briefing these early 20s airmen were told that they should consider themselves already dead, “It would be a lot easier that way for them.” When asked if he were scared, “Of course I was scared, only a damn fool would not be scared” Sandy said. Sandy thought his best-case scenario to survive the war would be to be shot down and made a POW, and it was not until after his 17th mission that he thought he could obtain his 25th mission goal.

In the winter and spring of 1943, the only fighter escort which the Allies could provide the B-17s covered a shallow arc barely extending to the Paris-Cologne area. Deep penetration raids were doomed to murderous losses until long-range fighters became available in 1944 to defend the bomber groups. The Eighth Air Force bombed during the day to see well enough to help ensure their bombs avoided civilian life and actually hit their strategic military targets. So fierce was the combat and loss of life, it was the Air Corps’ policy to rotate the air crews out of combat after reaching the magical number of 25 combat missions. Sandy, starting in December 1942, reached that magical 25 number on July 26, 1943, 12 days after his 22nd birthday. Only about 37% in Sandy’s Squadron made it to the 25-mission mark; the rest were either killed in action or made prisoners of war. The pilots were bunked three men to a room, and Sandy and his roommates were obliged to pack up the belongings of four roommates who failed to return from their missions.

After B-17 combat duty in Europe, Sandy was assigned to ferry command. He was checked out in the P-38, P-39, P-40, P-47, P-51, C-47, C-54, B-24, and B-25. Mostly he repositioned B-17, B-24, C47 and P-38s within the US. Later he was transferred to Air Transport Command in the Pacific Theatre (during WWII it was rare to fly in more than one theatre of action) flying C-54s carrying wounded soldiers back from the front lines to the hospitals in the rear. Sandy’s father, Lt. Colonel Welborn McMurray, was captured early in the war by the Japanese. It was on a medical evacuation flight to the Philippines when Sandy learned that his father, Welborn G. McMurray, a World War I veteran, had died June 14, 1942 as a prisoner at the Japanese Cabanatuan Prisoner of War Camp.

One of Sandy’s greatest moments during the war was flying a C-54 over Tokyo Bay during the Japanese surrender ceremony which took place on the deck of the battleship U.S.S. Missouri.

Reaching the wartime rank of Major, Sandy was awarded the US Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with 3-Oak Leaves Cluster, and Presidential Unit Citation for his military service. On January 20, 2011, Sandy was appointed a Chevalier (Knight) of the Legion of Honor by the President of the French Republic in gratitude and appreciation for his personal and precious contribution to the United States decisive role in the liberation of France during World War II. Sandy accepted the honor on behalf of all the air and ground crews of the 8th Air Force and then donated the medal itself to Seattle’s Museum of Flight for future generations to view. In the letter awarding the medal, it states, “The Legion of Honor was created by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1802 to acknowledge services rendered to France by persons of great merit. The French people will never forget your courage and devotion to the great cause of freedom.” While membership in the Légion is technically restricted to French nationals, foreign nationals who have served France or the ideals it upholds may receive the honor.

Returning to civilian life, Sandy flew DC-3s for United Air Lines based in San Francisco. The published story was that his mother staged the “chance meeting” on a flight. In December 1946, during a particular flight on which Sandy’s mother was a passenger, she spotted what she considered an acceptable wife for Sandy. The story was that Sandy’s mother wanted to ensure that they met so she asked Marjorie if she would please confirm her son was flying the aircraft. When Marjorie inquired on the flight deck whether Sandy was flying, she soon discovered that both son and mother already knew each other was onboard. At the time of their first meeting, Marjorie Stuard was based in Seattle. As luck would have it in September 1947 Sandy was reassigned to the Seattle base where he rekindled the spark from their first meeting, and they were married December 6, 1947.

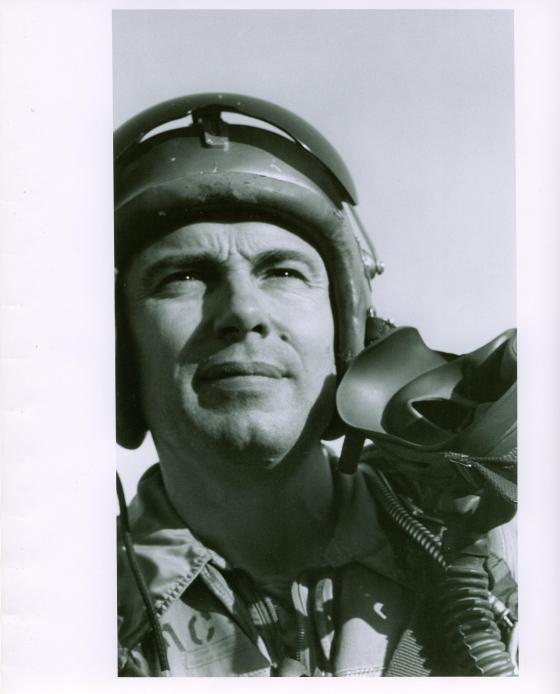

In 1949, Sandy became a Boeing test pilot flying the piston- powered Model 377 Stratocruiser and KC-97 tanker aircraft. The jet age began for Sandy with Boeing’s first jet, the B-47. This was aviation’s first swept-wing jet bomber offering. Beyond its military importance, the B-47 paved the way for the B-52 and KC-135, and the swept wing commercial air transport- the 707 and its successors.

In the late ʹ40s and early ʹ50s, as part of Boeing Production Flight Test, Sandy spent considerable time participating in the development of the new system of air to air refueling, a system that used a flying boom to transfer fuel from tankers to bombers. With air to air refueling, the B-47s could range the world as the carrier of the US’s nuclear deterrent. From the B-47 Sandy moved on to flight testing the considerably larger B-52 heavy bomber and the KC-135 jet tanker/cargo aircraft.

In the late ʹ50s, when Boeing introduced their famous first commercial jet aircraft, the 707, the Boeing jet test pilots were assigned to the flight crew training “faculty”. The Boeing test pilots had lived with the 707 program from its inception, and most of them now had jet experience dating back to the late 40’s. It was a challenge to train commercial “piston pilots” with 20+ years of experience how to fly a very unforgiving jet. This was before the advent of commercial jet flight simulators and pilots had to train in the actual aircraft. A major problem teaching senior captains, with a lifetime in propeller aircraft, was how to keep ahead of the considerably faster 707, when everything just happened just a lot faster.

During this training period in the early ʹ60s, and later during the aircraft acceptance process by the airlines, the German airline Lufthansa and the Japanese airline All Nippon would send their best pilots to Boeing. Sandy frequently invited these former WWII pilots home for Thanksgiving dinner and the former combatants shared their respective wartime flying strategies while at the same time lamenting about the folly of war over a turkey dinner.

From 1966 through his retirement in 1981, Sandy managed Boeing’s Production Flight Test, the department with responsibility for flight testing the 707, 727, 737 and 747 jet aircraft after manufacturing through to acceptance by the airlines’ pilots. Sandy and his Boeing colleagues literally had to write the procedures book on how to flight test production commercial jet aircraft. It had never been done before in such numbers. Frequently, Sandy and his crew would deliver the jets to the airline at their home base. Many times, on these international delivery flights, Sandy would invite along his favorite flight stewardess, Marjorie for a vacation after the aircraft was safely delivered to the customer.

In Sandy’s opinion, he experienced the best of aviation by participating in the transition from piston powered aircraft to the early day jet aircraft. In Sandy’s words, “high technology jet aircraft are great achievements, but from a pure joy of flying perspective, it is a lot more fun to do the flying by hand than turn it over to the computers and the direction of ground controllers. I had the best”. Sandy retired in July 1981 as Chief of Production Flight Test, a position he had for 15 years.

Sandy’s love of flying did not begin, nor did it end with his Boeing career. Beginning in the early ʹ70s, Sandy owned several single engine private Beechcraft Bonanza aircraft. The typical recreational day of flying for Marjorie and Sandy in retirement, and before retirement on weekends, was to fix a picnic lunch in morning, fly from Seattle to any one of several Western Washington airports, hop in their previously positioned airport beater VW bug, drive to a secluded beach or park, eat lunch, and then return home later the same day. Destinations ranged from the San Juan Islands, Mt. Baker, and Hurricane Ridge. Sandy was a member of the Quiet Birdman-Seattle Hangar for many years.

Sandy’s non-flying interest revolved around his family, managing his real estate and stock investments, and playing the neighborhood fix-it man with his well-equipped shop. He is preceded in death by his wife Marjorie, son Mike McMurray, and sister Elizabeth Wiggins. He is survived by his daughter Patti Pierson, and her children Christie Fankhauser (Brad), their children Cole, Erin and Ella, grandson Brian, and his son Scott Sanford McMurray.