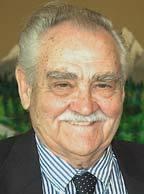

Morrie is a great guy to meet

Mon, 06/18/2007

I'd like to tell you about my new hero, Morrie Skaret, but he's 94 years old, and there's no way I can tell his story in one week.

Not even Morrie could do that, and Morrie is a heckuva storyteller. But bear with me, and I'll tell you the rest next week.

Morrie has been your neighbor in West Seattle since he got a job as the first lifeguard at the original Colman Pool in Lincoln Park, so long ago that most of you were not born yet.

Morrie was 18 and the pool then was merely a low spot on the edge of the sound.

The city had scooped out a deep hole and the tide filled it with saltwater. It had a sandy bottom. Every so often they took a bucket of the water and put a chemical in it to test for urine because most kids just let it fly instead of running to the toilet.

When the tide went out the kids would take buckets and gather tiny sea creatures, small crabs and the like wriggling in the sand and put them back in the sound. The tide would come back later and refill the swimming hole. Eventually the city decided to replace what they called a mud hole and Colman Pool was born.

Morrie was a good swimmer. He had learned how in a small slough on his parent's homestead way up in northern Calgary. His parents were given 160 acres from the queen and they lived in a sod house with three kids, two oxen and one plow.

Scratching out a meager existence growing oats and wheat, they barely survived after leaving their native Norway seeking a better life. The floor of the house was mud, scraped off the bottom of the small slough. It dried hard as cement and could be swept without raising dust.

More than 90 years, later Morrie has instant recall and a remarkable memory. He is 6 feet 3,190 pounds, and is sharp as a razor.

He recalls living through a couple of bitter Northerns, a term for gale force winds and temperature 40 below.

Sometimes it got so cold his dad had to bring the two oxen into the sod cabin at night to keep them from freezing. In the morning his mom had to scoop the manure out the door with a shovel.

To this day Morrie says he loves the smell of manure.

The tiny house had a coal burning stove for heating and cooking. They lived a few miles from a dealer who provided hard anthracite, which burned slowly and kept the cabin tolerable all night. Even so, some nights got so cold the kids curled up under the parents' blanket on top of their mom's feet to keep her toes from freezing.

Morrie and his brothers and sisters were raised on rolled oats for breakfast and to this day he eats rolled oats each morning.

They grew the oats, soaked them in a barrel of water with vinegar, drained the liquid off and then wrung the puffed up slurry through a homemade wringer.

Dried, they poured milk over them, added some brown sugar and that was breakfast.

When Morrie was only six his dad named him Keeper of the Pigs. It was his job to slop 14 porkers twice a day and catch them when they broke out of the pen. As far as I know, he never shared any of his rolled oats with them.

Life got so tough his parents decided to go south and abandon the prairie life.

When he arrived in West Seattle with his family in about 1913, he met Rupert Hamilton who was publishing the West Seattle Herald. Rupert was looking for carrier boys and paid Morrie a penny each to deliver to 500 homes every Thursday after school.

(Naturally, I told Morrie that route is still available. He turned it down but I believe he could still do it. I suppose he'd want 2 cents apiece the way the cost of rolled oats has gone up.)

When he got the job as lifeguard he sat on top of a high tower and watched swimmers and sunbathers. One cute little French girl lying in the sand caught his 18-year-old eye and after some conversation he offered to walk her home, three miles out of his way.

That walk led to many more and a year later she became his first wife. Her name was Marjorie Dorais. Tragically, she died of cancer after only 20 years.

To hear the rest of Morrie's story, tune in next week.

Jerry Robinson can be reached at Publisher@robinsonnews.com