REI started in this West Seattle attic

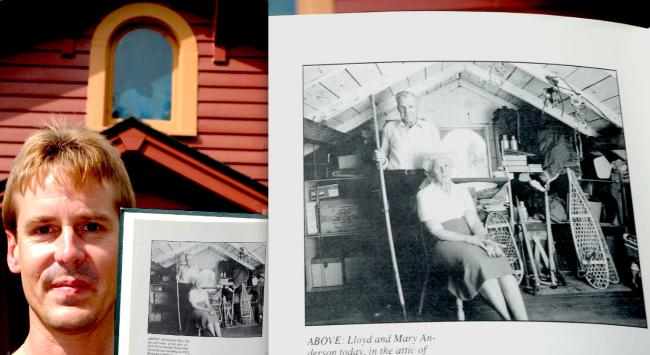

SUCCESS IN COOPERATING. West Seattle architect Tim Rhodes stands in front of the house he refurbished where Lloyd and Mary Livingston lived. They started REI in their attic, behind the oval window pictured on left. They are pictured in the attic in a book Rhodes holds. The same oval window is visible next to them.

Mon, 08/30/2010

One of the many delights of West Seattle living is beholding the majesty of Mount Rainier, when it is “out,” and while most onlookers will never ascend her face, those who do may first hike into REI for a climbing course and gear.

The 100-plus stores of REI, or “Recreational Equipment Incorporated,” headquartered in Kent, with that eye-catching anchor store of stone, waterfalls, and glass in downtown Seattle just west of I-5, quietly began in 1938 in the attic of Lloyd and Mary Anderson’s farmhouse on 4326 Southwest Southern St., about a mile southwest of the Morgan Junction.

Lloyd came from rural Roy, south of Spanaway, Mary from the Yakima Valley. They met as UW students at the University Commons while dining there on the cheap. According to the book REI: 50 Years of Climbing Together, mountaineering was reserved for the upper crust.

The book describes the Andersons: “Neither of the pair belonged to the comfortable urban class which found conscious pleasure in walking, but since neither of the families owned automobiles until late in the 1920’s, they walked- constantly.”

Lloyd climbed Mount Adams with four companions Memorial Day weekend, 1930, then Glacier Peak and Mount Olympus over the 4th of July break. Six days home from Mount Olympus he was atop Mount Rainier. The following year Mary climbed eight summits. They had both joined The Mountaineers shortly before that, and wed in 1931. They built the house on about a half-acre overlooking the Sound with a prominent view of Blake Island.

REI germinated from Lloyd’s desire to purchase an ice axe in 1934. Seattle’s Outdoor Store sold the tool for $20, which, according to the REI book just cited, was the price of 240 pounds of lean ground beef. He settled for a $7 axe that cost an additional $5 after shipping, and came from Japan, not Austria as promised. Unlike today, Japan gear had a stigma of low craftsmanship. The Andersons then bought an Austrian catalog with ads of outdoor equipment and, aided by Mary’s knowledge of German, sifted through and found high quality, low-priced climbing tools.

A gathering of the Andersons’ climbing colleagues each pitched in one dollar in 1938 to join the “Recreational Equipment Cooperative” that would become the iconic REI. Dividends from profits were paid back to members, all volunteers. Goods sold for about 25-percent less than prevailing prices. The co-op sold dehydrated food, and even silk hosiery, towels and members got gasoline discounts of two cents at one member’s filling station.

As they say, the rest is history. While their co-op moved to Western Ave, the Andersons lived in the house until Lloyd passed away in 2000 at age 90. Mary, who now lives in a retirement home in Ballard, listed the house while still living there. A group of eight like-minded investors who wanted to make a profit, but not at the expense of the aesthetic of the property, bought the house and property about a year later. They were The Neighborhood Company. They modernized the Anderson’s house and built three others on the lot, with a common garden and some shared garage and parking space. Their vision was a sort of townhouse/commune combination in the spirit of the cooperative ideal.

Group members, architect Tim Rhodes and his wife, professional light-designer Susan, helped design the homes. They fell in love with the anchor house, and bought it. They reside there with their two children and pet cats. Tim was quick to credit West Seattleites Jeff McCord and wife, Rosemary Woods who headed The Neighborhood Company. They were the driving force of the group, according to Rhodes.

“The house was originally something between a craftsman, bungalow, and farmhouse, hard to categorize,” said Tim Rhodes, of Rhodes Architecture and Light. His studio is in the Alaska Junction, just above Cupcake Royale. “Mary had tried to sell it for almost a million dollars, then came down to just under $700,000. Then the group incorporated and offered 649,000. Mary turned to her attorney and said she want this group to have the property. She was an avid master gardener and spent many years with the garden.

“I walked up the driveway and was absolutely flabbergasted,” recalled Rhodes with surprise in his eyes. “It had a huge lawn with a lot of rose gardens, fruit trees, a stupendous view, and was tucked away. I got onboard initially as an architect to design it, with no realization that it was possible to buy it. The Neighborhood Company was a way to do community-based development sensitive to the site and to be involved in the history of the site. I did some quick sketches that the group showed Mary. Her heart was really in the right place. It was probably very hard for her to leave. She raised her daughters there. She took a (financial) loss, I think, to see the property developed in a responsible way. She was engaged with the process.”

The Anderson house is now 2,668 square feet. The other three are less than 2,000 square feet. All are four-bedroom, two-bath homes. One is currently on the market. Rhodes said their house is plenty big for his family’s needs.

“I think houses are too big in this country and I feel very strongly that we’re living in far too many square feet and are very intensive in energy and material use,” he said. “At the end of a life of a house, it has to be torn to the ground, loaded into a dumpster, and hauled to a landfill. I think it’s wonderful that the (Anderson) house has been renovated, and brought up to current codes and standards to last at least another 50 years. It can then be renovated again and again, and that legacy will live on. I think the Andersons were very much about frugality, living on the land.”