The Alki Homestead is on the road to restoration

Built in 1903-04 the Fir Lodge, later to become the Alki Homestead is finally on the road to restoration, if agreement can be reached with city agencies responsible for the management of historic structures.

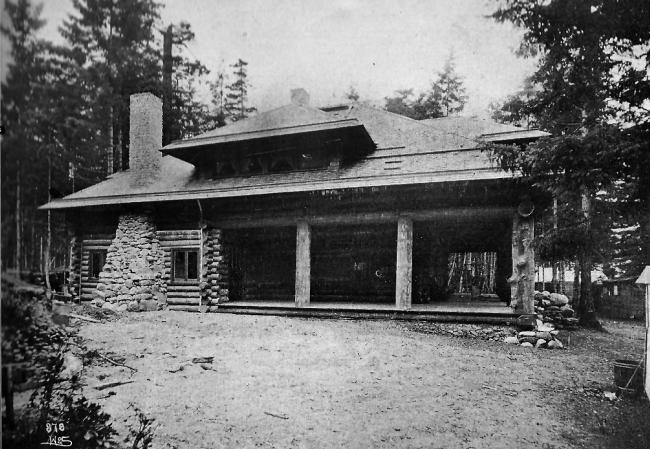

This view is the east side of the building. The original entrance was on the north side. You can see in this image the original porch, which was later enclosed when the building became a restaurant in 1950.

CLICK THE PHOTO ABOVE TO SEE MORE

Thu, 01/27/2011

The Alki Homestead/Fir Lodge has been the subject of a great deal of controversy and public attention in recent years. It was named as an Historical Landmark in 1996. It suffered a fire in 2009 and has been boarded up since that time. It's been the subject of press conferences, public gatherings, speeches and many conversations.

Finally, it is on the road to restoration.

What that means and how it happens will no doubt be subject to public and official scrutiny. The West Seattle Herald, in an exclusive interview with the owner and architects, has seen the details of the plan.

Owner of the building Tom Lin has, with private investment funding, quietly assembled the information and people necessary to bring the facility back to life as both a working restaurant and banquet/meeting place. That's both his vision and that of the architects he has hired to make it happen. But before that can be explained and understood, some background on the building, how it began and evolved is important.

History

The Alki Homestead at 2717 61st SW. was built in 1903-1904 by Fred L. Fehren and Anton Borgen, and was originally known as the Fir Lodge. Commissioned by the owner and manager of the Seattle Soap Company William J. Bernard and his wife Gladys it was built in the "Rustic Style" out of Douglas fir logs. It cost $5000 to build. No plastering was used in the original construction.

The original plans say it was built to be "51 feet 6 inches square(…) with 8 rooms, having 4 bedrooms on the second floor. A large living room, which is 20 x 30 feet, is surrounded on three sides with a 10 foot porch."

At the time, Alki was largely dominated by cabins and summer camps. After three years the Bernards moved out and sold it to an organization called the Seattle Auto and Driving Club, who also bought the adjoining carriage house, which after years as a residence would later become the Alki Loghouse Museum. Over the ensuing years as more and more people came to visit and live in the beach community the house was used as a private residence and a boarding house.

TO SEE THE HOMESTEAD/FIR LODGE AS IT ORIGINALLY APPEARED VISIT OUR FLICKR GALLERY

In 1950 Swend Neilson and Fred Fredrickson purchased the building and converted the Fir Lodge into a restaurant they named the Alki Homestead. Numerous changes were made to the building throughout this period and later external buildings were added to the southwest corner in order to accommodate a larger kitchen and storage.

Walter and Adele Foote bought it in1955 and sold it five years later to Doris Nelson. It was Nelson who really made the facility come alive by establishing the theme, bringing in antiques and offering family style cooking, including her famous fried chicken dinners. Nelson ran the entire business personally and lived upstairs with her two children. The Homestead remained in constant operation from then on as a popular place for social gatherings and parties.

In recognition of its history, the Landmarks Preservation Board (LPB) designated it as a Seattle Landmark in 1995 with approval by the Seattle City Council coming the following year.

In 2004, Nelson, then aged 80, passed away and the Alki Homestead was offered to Southwest Historical Society with first right of refusal. The president of SW Historical Society, Joan Mraz, approached Historic Seattle to purchase the property, but was turned down. Then Ms. Mraz approached several local citizens including Tom Lin in 2004 to buy the Alki Homestead for the Society but was also turned down.

It was not till the summer of 2005 that Tom Lin was approached again by Larry Carpenter, who was serving on the board of SW Historical Society,that he decided to step in and save the restaurant. It was purchased by Tom Lin and Patrick Henley in 2006 for $1.25 million. They continued to operate the business just as Nelson had but since the restaurant industry was not their forte they chose in March of 2008 to sell the business but retain the building. The asking price for the business was $495,000. Patrick Henley decided to pursue his passion in construction and left Alki Homestead to Tom Lin as sole owner.

A buyer was found in November 2008, but before the deal was finalized, a fire caused by overloaded Christmas lights happened on Jan. 16, 2009, Damage to the building was extensive and restoration was estimated to cost $1.65 to $1.8 million.

Since that time the building has had numerous inspections and detailed engineering reports. It has also been the site for rallies sponsored by the Southwest Seattle Historical Society whose theme of "This Place Matters" is part of a campaign by the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

Lin, in the ensuing period has sought loans to pursue restoration but found the lending market to be too tight. He has sought investment partners without success. He has offered the building for sale to any historic preservation organization and last year set the price at $2 million but offered to refund $500,000 as an endowment to assist the restoration. A coalition of organizations led by Historic Seattle began to negotiate with Lin last year but the two parties could not come to an agreement on price. Lin finally sought and found a private investment lender in the last few months and has hired Alloy Design Group to develop the plans for the project. The funding of the project is to be finalized in coming months.

As part of the preparation for restoration, Leavengood Architects were hired last September by Historic Seattle to prepare a Building Assessment Report. It's attached as a downloadable file to this story. It was released on Oct. 8, 2010 and they are very clear about the urgency to take action soon, quoting from the report:

"The information within this report reveals that while the structure has suffered wood rot, powder-post beetle damage and charring from fire the building remains restorable. There is still remaining sufficient historical fabric in place, in spite of re-modelings, additions, and deferred maintenance for the building, to consider it viable to continue to contribute to the historical character of West Seattle. This log structure is unique in its architectural design quality to warrant an effort to save the structure from demolition. However with the accelerated decay due to the fire damage and wood rot, time is running out for this restoration to begin. If left many more months to damaging intrusion the structure will only accelerate its degradation and decay. Therefore the team strongly recommends that a ‘restoration/rehabilitation plan’ be formulated quickly in order to establish a realistic construction budget."

Who is doing the work? What are they planning?

Alloy Design Group is an architectural firm in Seattle comprised of Greg Squires and Mark Haizlip. While Alloy as a firm has only some experience in historic building restoration Lin chose them he said, "Because they are young, smart and have great energy…and I wanted to give them a chance on a unique historic project."

In an exclusive interview with the firm they detailed some of the background of the project and how they arrived at some of the design choices they made.

"The bottom line is we're restoring the building," Squires said " but that poses the question of what that means. To what level, or point in the building's history will it be restored?” Squires explained some of the definition of that based on the official description provided by the Secretary of the Interior, "Deteriorated features from the restoration period will be repaired, rather than replaced. Where the severity of deterioration requires replacement of a distinctive feature the new feature will match the old in design, color, texture and where possible materials."

The architects have met with Mark Fritch; his great grandfather Anton Borgen built the Fir Lodge/Alki Homestead. Mark Fritch is also an expert log home builder from Oregon who served as a consultant on the restoration of the Alki Log House Museum building and who will likely be part of this project going forward. In their discussions with him they learned a great deal about log construction. Haizlip said, "We want to match as much as possible but the difficulty is, the understanding of how to build a log structure has changed over the last hundred years (…) Do you repeat mistakes of the past? Mistakes that he said his great grandfather would admit. Or do you try to improve upon them, at least a little?"

Haizlip suggests improved methods and construction techniques might be employed but kept largely hidden.

Squires added that in Fritch's opinion was that "They hadn't intended for this building to be here 100 years (…) and part of his reasoning for that is the simple overhangs. To build a wood structure and only give it a two foot overhang… you're not building for 100 years." "One of the ways it was originally built was with a wrap-around porch. The main exterior walls of the house are inset eight feet from the outside of the building," Haizlip added, "It was later enclosed but originally it was unconditioned space, then made into conditioned space."

"What we're going to do is develop a restoration plan," said Squires,"(…) When you look at the Secretary of Interior's standards you pick a point in time to restore the building back to. It's a discussion with the Architectural Review Committee and ultimately with the Landmarks Preservation Board. It's going to be a hybrid of a point in time. (…), the reasons being that some of the additions that were made to include that kitchen are not historic. In fact in some of the reports (referring to the extensive engineering studies), they go on to say they really butchered up the building. (…) So part of the restoration plan is to restore both the east and the south facade. At the same time we're going to be restoring the restaurant. So we're going to be restoring the south facade to a point in time that's probably closer to the 1940's but the rest of the building, regarding the restaurant would be restored closer to when it became a restaurant or something closer to the 1950's."

Squires and Haizlip wanted to emphasize that "This is an open discussion. It needs to be informed by their (the LPB) expert opinions. At this point nothing is chiseled in stone."

While the discussion regarding the specifics of restoration is open, it's clear that the building will need to make economic sense for Lin. The final form of the building will also have to adhere to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Their plan calls for the demolition of the south and west facades which were add-on in the 1950's, then reopen banquet/meeting space on the second floor, the creation of a new structure on the west side of the building which would house a new kitchen and ostensibly a "just tall enough" structure to permit the installation of a staircase and elevator to provide access to the second floor for ADA purposes. What that new structure looks like is not yet clear but it is Alloy's intention to make it visually consistent but non-distinctive, meaning it will be essentially hidden behind the primary Homestead building so as not to detract from its appearance. There are three potential profit centers in the building: the restaurant, the lounge and the banquet facility. Of these the "trickiest one is the banquet facility only because a facility that size would have to be located upstairs," Squires said. A banquet facility has to be included in order for the structure to be economically viable.

Given the ADA requirements and the need to make the numbers work, certain changes are required. "The existing stairs are non-conforming and there's no way to put an elevator in the building without putting it right in front of the fireplace," said Squires.

Based on Lin's business plan, the banquet facility would average 80 to 85 people per event. In the plan, lunch would serve 40 to 50, and dinner 80 to 85.

"Our goal is to strip the structure of the non-historic elements," said Haizlip, though the neon sign would be restored and retained.

Squires concluded, "If you distill down what everybody wants it's actually the same thing, and that is to get this restaurant restored and back in action."

As Alloy states in their Pre-Submittal Conference Application:

Restoration of the historic Fir Lodge/Alki Homestead Restaurant, demolition of the non-historic accessory structures (at southwest portion of the structure), and new construction of an attached kitchen/storage facility at the northwest portion of the site (between Homestead and Alley). Existing parking to remain.

-Verify setback requirements at West and North property lines

-Verify height allowances (for new kitchen/storage facility).

-Discuss non conforming portion of Homestead and North property line.

-Discuss proposed scope of work to obtain questions and or concerns from the DPD and the Dept. of Neighborhoods.

-Discuss any issues the DPD and Dept. of Neighborhoods foresee arising as we move forward.

-Verify "restoration" requirements/allowances.

Alloy is meeting with the Architectural Review Committee (ARC) on Jan. 28 but part of the difficulty with a project of this scope and importance is that they are only allotted 30 minutes and the committee, comprised of volunteers only meets once a month. Hence the presentation and discussion must be condensed and concise.

If they can pass muster with the ARC over the course of a few meetings the resulting plan will come before the full Landmarks Preservation Board. Once they give their approval, the restoration process can begin.

How do they go about it?

Restoring an historic building can mean following a very precise deconstruction process in which each part is carefully marked, evaluated and removed. If deemed salvageable it is set aside. If not, it's replaced. Old photos, plans and other buildings are studied to painstakingly preserve, if not the full intent of the original designer and builders, at least the spirit of the building. There are a lot of photographs of the building as Alloy has discovered and these will prove helpful in guiding the restoration process. They plan to offer a lot of communication to the community to keep a clear idea of where they are in the process.

But Lin and his architects will be in the discussion and review phase for some time. Their best guess as to when the Homestead might see a reopening is some time in 2013 or two years from now.