Cost Benefit Analysis on West Seattle Bridge points toward repair or super structure replacement

Tue, 10/20/2020

The long awaited Cost Benefit Analysis (CBA) for how to solve the problem of the broken West Seattle Bridge points toward two most likely choices.

SEE SDOT CBA READER GUIDE

AND COST BREAKDOWN HERE

Rehabilitation and direct strengthening to restore the live load giving the bridge another 40 years of service at cost of $916 million total; $47 million upfront or superstructure replacement giving the bridge another 75+ years of service at a cost of $1,005.7 million total, $383.1 million upfront.

While being careful to point out that Time, Space and Location studies would be required for any choice the City makes, those two alternatives stood out in terms of the attribute weighting that was established by the Seattle Department of Transportation. The repair alternative showed the greatest return on investment and bring bridge back on line in 2022. The superstructure replacement would allow light rail to be added later according to WSP. It would bring full traffic capacity back to the bridge by 2026.

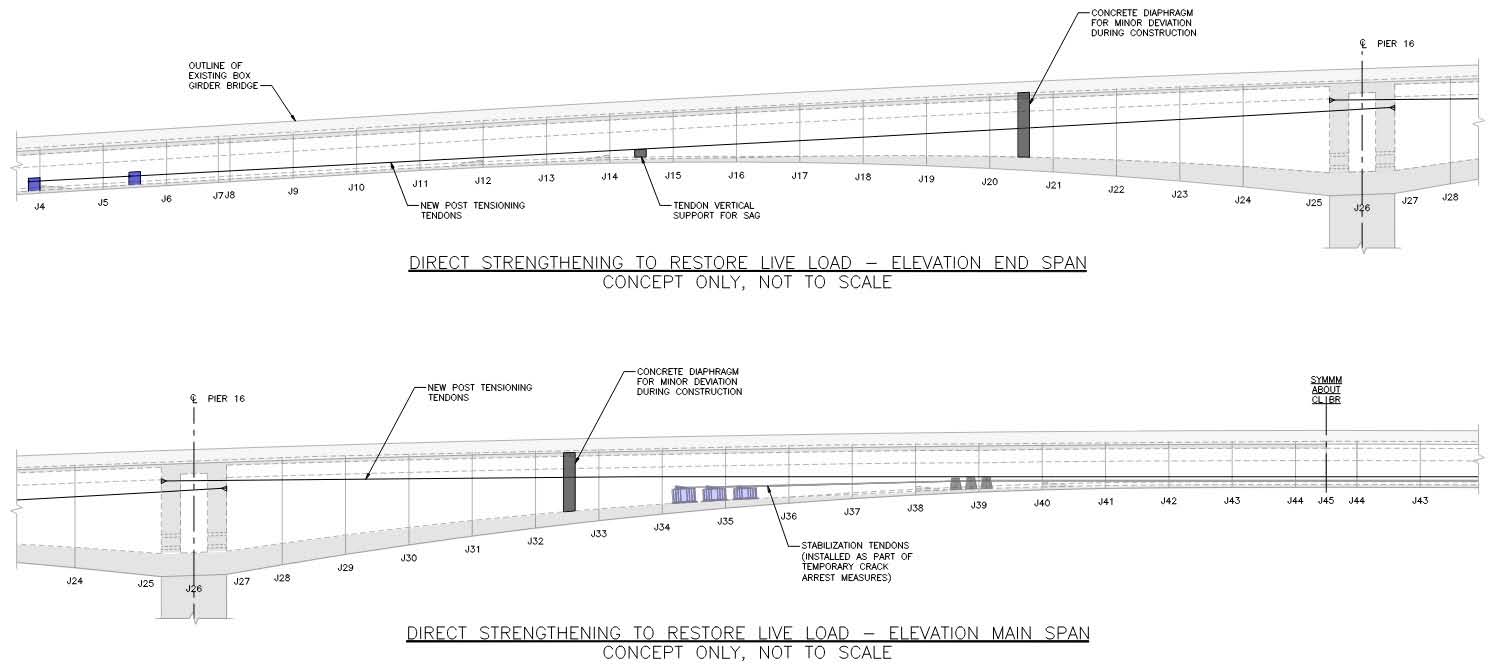

From the report regarding Alternative 2:

"The direct strengthening to restore live load (rehabilitation) concept consists of post-tensioning inside all spans of the box girders. The strengthening would restore capacity to the distressed regions so that live load could be restored to original condition for the bridge’s remaining service life (40 additional years).

Currently, the WSHB is undergoing stabilization work, which also includes external post-tensioning. It should be noted that this proposed alternative would require a more comprehensive version of current stabilization measures."

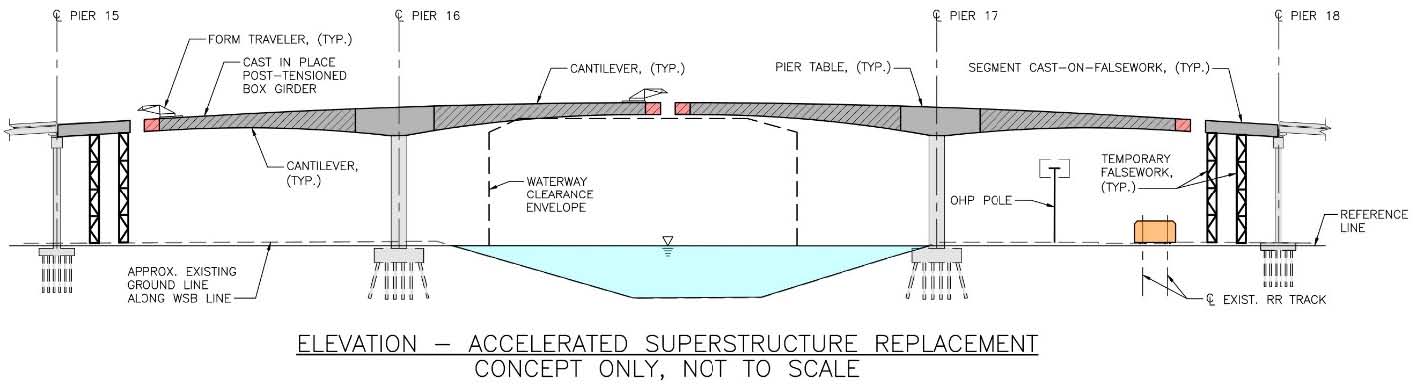

From the report regarding Alternative 4:

"The on-alignment superstructure replacement involves demolishing the existing box girders between Pier 15 and Pier 18 and replacing it with another box girder superstructure, reusing the current foundations and substructure.

(The illustration) depicts how a superstructure replacement could be constructed using the balanced cantilever method, like its original construction. As with the current bridge, segments would be composed of cast-in-place post-tensioned concrete. Construction would require temporary falsework support.

If determined to be adequate for today’s standards, the columns and main pier diaphragm reinforcement would be reused. Preliminary analyses indicate that the foundations would need some level of retrofit to support the new superstructure. However, unlike Alternative 2, which could accommodate a retrofit later, Alternative 4 would require a retrofit concurrent with superstructure replacement. Alternative 4 would be future compatible with light rail and restore traffic to its original capacity.

The other alternatives, including the much discussed Immersed Tube Tunnel did not fare well.

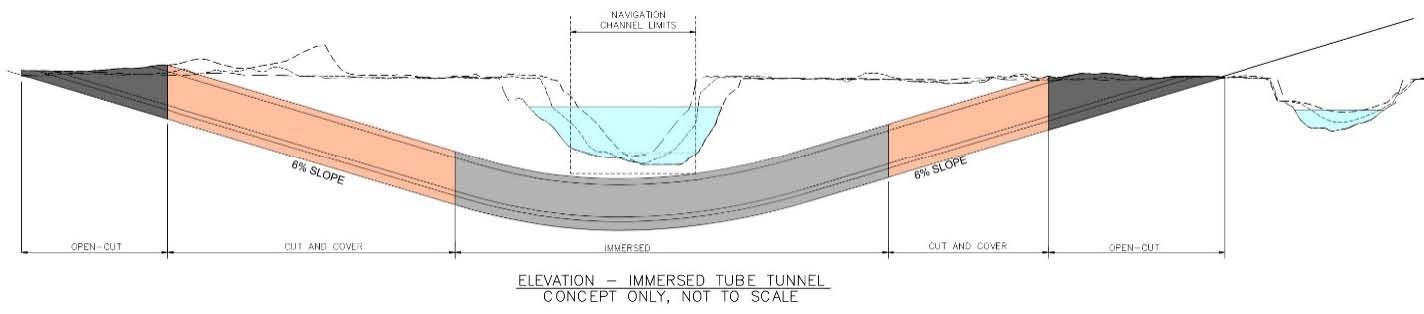

From the report regarding the Immersed Tube Tunnel:

"WSP considered two immersed tube tunnel alignments, located to either the north or the south of the existing WSHB. The tunnels connect to the surface network via cut-and-cover and open-cut segments (see Appendix L in the full report for more information on tunnel concepts). WSP reviewed multiple alignments to the south and north of the existing corridor. Future studies should further evaluate the pros and cons of each alignment but, for cost estimating purposes, we chose the northernmost alignment to correlate with publicly presented alignments. There may be advantages to aligning the ITT to the south to minimize impacts with the railroad and Port of Seattle property.

The ITT segments would consist of reinforced concrete and be fabricated off site in a concrete casting basin facility.

While not included in the CBA, if the tunnel included light rail, it is likely that a casting basin would need to be constructed, as there is no regional facility large enough to accommodate the fabrication of concrete tunnel segments of this magnitude.

After casting, each segment would be floated to the site prior to immersion and connection with adjoining segments.

Cut-and-cover segments would also consist of reinforced concrete but would be constructed on site. A typical tunnel section and the tunnel profile for the north alignment are provided below.

Gregory Banks, PE, SE and Project Manager for SDOT consultants WSP, was the author of the report. He states in his cover letter," This report is intended to support the City as it makes the decision related to rehabilitation and/or replacement. As we understand through discussions with the City, the CBA is just one element out of many in making that decision. As such, the CBA presents findings in the form of value indices, which is a measure of return on investment, but does not provide any recommendations or conclusions.

The CBA was conducted in an accelerated time frame and with limited information due to the emergency nature of the work. As such, we needed to make a number of assumptions.

Understanding the limitations and impacts of these assumptions within the CBA is important."

FULL STUDY IS HERE

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Because of observed accelerating crack growth in the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge (WSHB), the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) made the decision to close the bridge to traffic on March 23, 2020, commencing the West Seattle High-Rise Bridge Safety Project. This project, which is part of a larger program, comprises designing and installing an intelligent monitoring system, conducting non-destructive testing, developing an emergency response plan, designing and constructing bridge stabilization measures, and conducting a cost-benefit analysis (CBA) — the results of which are presented herein.

Project Overview

SDOT did not make the decision to close an arterial route upon which the people of West Seattle and the region depend lightly. Its closure has disrupted lives, as well as the mobility of freight, services, and goods through the region. The closure has negatively impacted already marginalized communities. It has affected the maritime industry and the operations of the Port of Seattle. The closure’s effects cannot be understated, nor can the consequences, should the bridge have failed during rush hour. From the outset, that this has been a public safety project. It continues to be a public safety project.

The intelligent monitoring system and non-destructive testing determined that it is technically feasible to continue further investigating if the bridge can be rehabilitated to restore live traffic. The bridge’s continued positive responses to ongoing stabilization work and the findings of the structural assessment of further rehabilitation and retrofit concepts, echo that feasibility. However, there remain key stabilization work activities, including the release of the restrained lateral bearing at Pier 18 and the installation and tightening of the external post-tensioning system.

These measures, to be completed in the coming month, are import to confirm these trends hold true.

The purpose of the CBA is to provide objective information and context to help the City decide between investing in further rehabilitation of the existing bridge or pivoting towards a replacement structure. The methodology incorporated multiple alternatives within that apparent binary choice. We assessed five alternatives using both quantitative and qualitative analyses for value determination and for risk and cost. Section 6 presents findings in the form of value indices (performance divided by cost, with costs inclusive of monetized risk).

WSP conducted the CBA on an accelerated schedule. We needed to make several assumptions, including selecting five conceptual alternatives based on apparent low cost. As such, the CBA does not represent a type, size, and location (TS&L) study. Should the ultimate decision be to replace the bridge, we anticipate that the City would explore yet-to-be-determined alternatives, some of which may be similar to the concepts presented here, but some of which will be different in type, size, and location, as well as in construction means and methods and material composition. Section 7 provides a detailed list of considerations for future studies that were beyond the scope of this CBA, because, as important as the findings are, so, too, is an understanding of what was not considered but should be in future studies.

This CBA addresses some of the questions we have all grappled with since March 23 – What long-term impacts will this closure have? Can the City afford to wait for a replacement? What is the life span of a rehabilitated structure?

What benefits does rehabilitation offer? What benefits does replacement offer? While the purpose of this report is to objectively present the benefits and drawbacks of multiple alternatives, to help inform the decision to rehabilitate or replace the bridge, its findings will not, and should not, dictate that decision.

The CBA is, in fact, just one factor in this decision, focused on helping to support decisions being made around public safety and technical risk. The decision will also be informed by external exigencies and current events, by the recommendation of the asset owner, SDOT, as well as by the guidance provided by the Technical Advisory Panel (TAP) and Community Task Force (CTF). Ultimately, the imminent decision to rehabilitate or replace the structure will be a City decision based on a value judgment for the safety and well-being of the people of Seattle.