The Schmitz Twins reflect on Seattle and family history

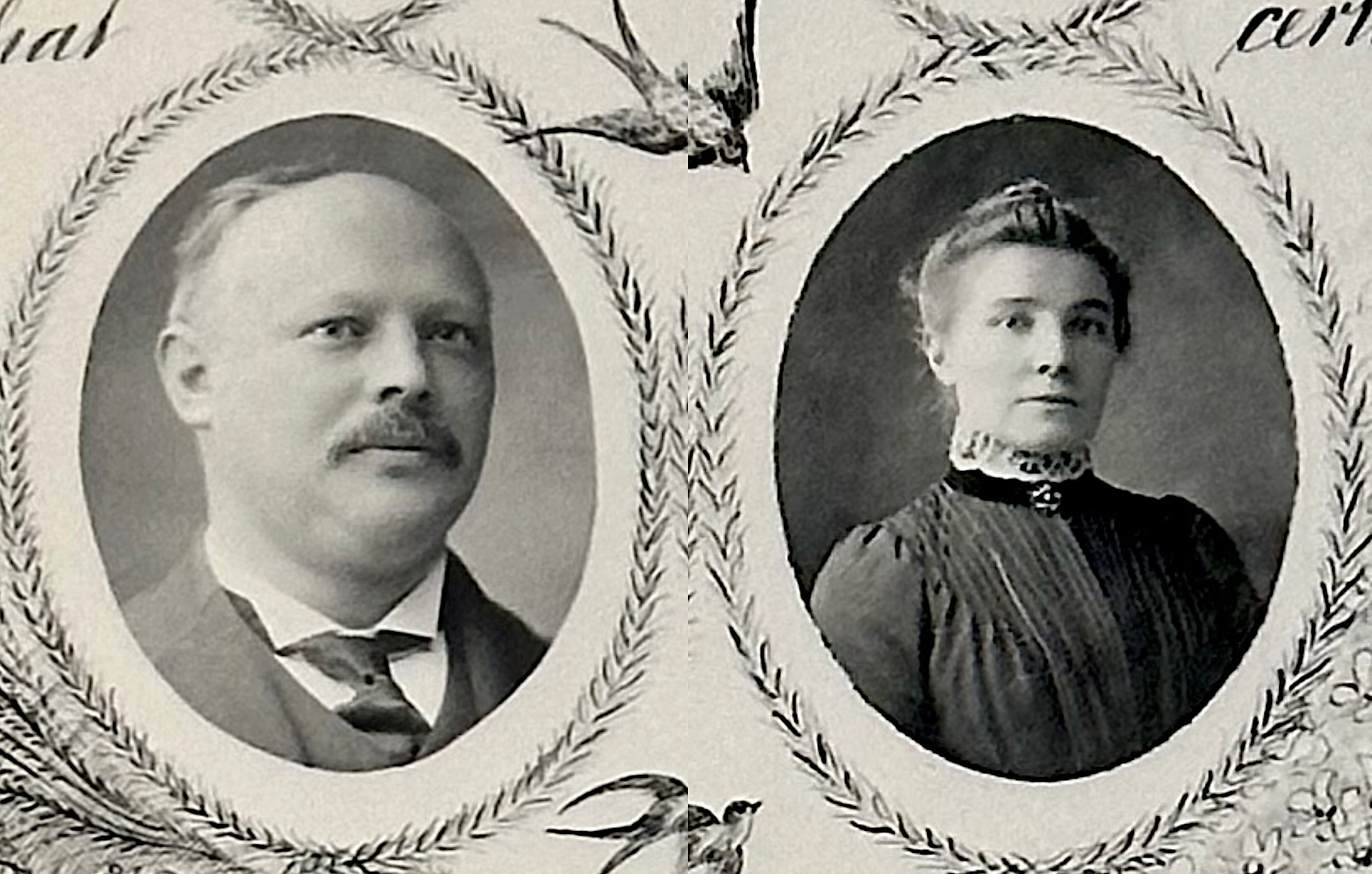

Patsy Ann Schmitz Carpenter, and Nancy Ann Schmitz Wilson are the grandaughters of Ferdinand and Emma Schmitz Seattle philanthropists who built a fortune and donated land to create parks in West Seattle.

Photo by Patrick Robinson

Fri, 10/25/2024

By Patrick Robinson

On the mantel above the fireplace in a hand built german style home in West Seattle were the words of a family motto “Do it now”.

They called the home “Sans Souci” french for “No worries” and for the Schmitz family it came to represent that same ideal of confident action and living in the moment.

The home was built by Ferdinand Schmitz whose personal impact on West Seattle and the larger community is still felt today in ways well known and others more subtle.

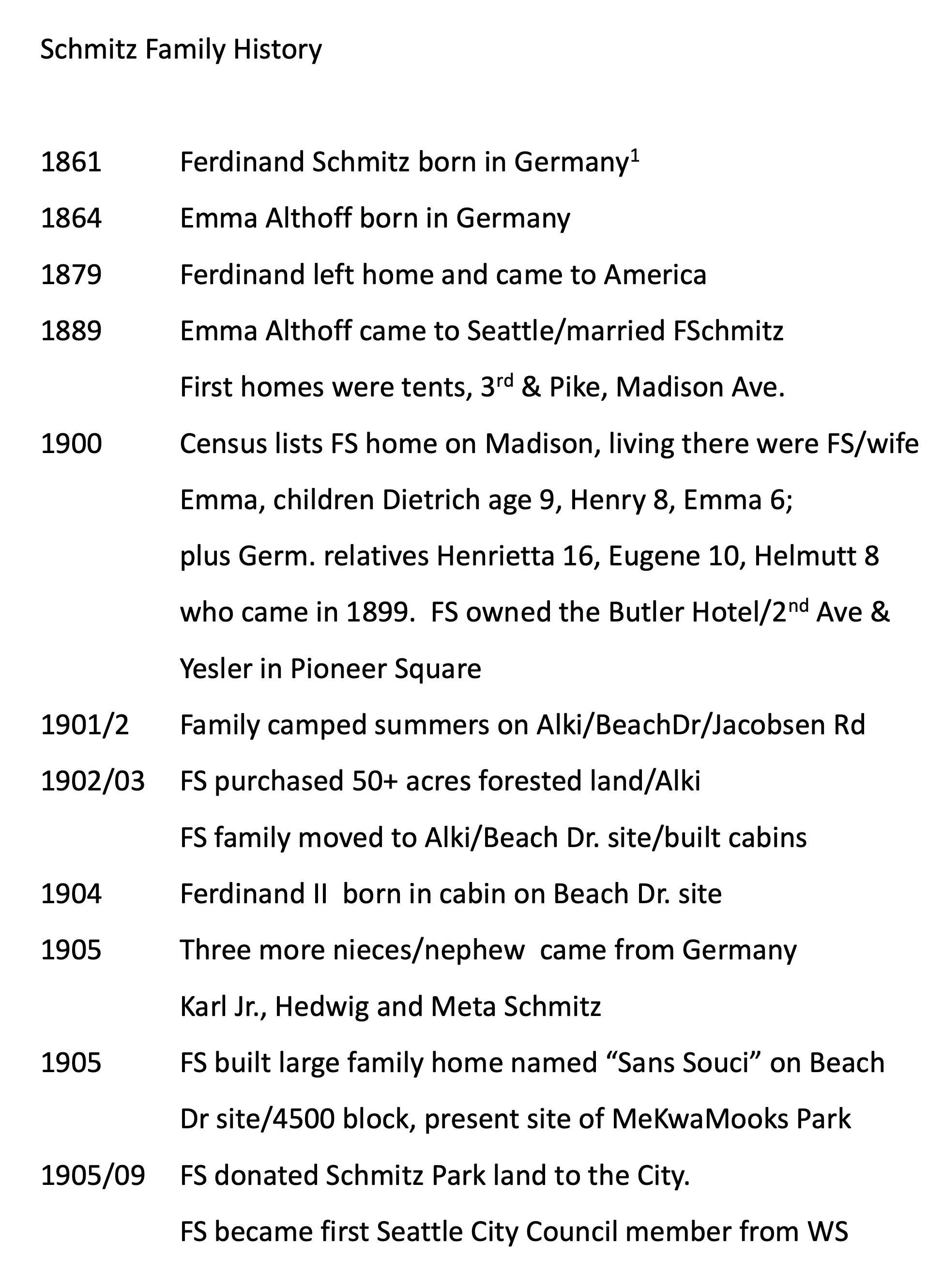

Born in Duisburg Germany in 1861 he was clearly given to both impulse and determination. He chose to leave his home to stow away aboard a ship bound for New York. No small risk, for a 16 year old but his oldest brother was due to inherit the family farm with nothing left for Ferdinand. The risk of imprisonment and being shipped back was worth it for chance at a new life. Then his fears came true.

He was discovered.

But rather than just lock him up they put him to work. The captain and crew planned to have him sent back to Germany but during their stop in New York something remarkable happened. Ferdinand was allowed to go with the crew as they toured the city. They stopped into a German bakery and the woman behind the counter must have taken a shine to Ferdinand because she improvised a plan. She must have known he was going to face punishment.

In those days women wore large “hoop skirts" and she told him to hide under hers. As the crew prepared to leave she told them Ferdinand had left and the crew figured he had just run off.

He was free.

Ferdinand worked at the bakery for a while, actually learning a trade, then bidding his protectors farewell made his way to Baltimore, Maryland, St. Louis, Missouri and Pomona, California where he was naturalized and traded on his baking experience before coming to Seattle in the late 1800’s. He made a trip to Germany where he proposed to his teen sweetheart Emma Althoff Some time later he journeyed to Seattle.

Ferdinand was by all accounts charming, a hard worker who saved his money, parlaying it into enough to buy land and buildings, with partner Dietrich Hamm whom he had met onboard the ship and by age 26 they formed a real estate company Hamm & Schmitz and had the restaurant/bar called the Rathskellar. The duo later ran the Butler Hotel from 1893-1903 at 2nd Avenue and James Street in downtown Seattle.

The hotel was originally a three-story wooden structure but in 1889 the most destructive event in the city's history, the Great Seattle Fire occurred. It destroyed 29 city blocks, four wharves and the railroad terminal. It began when an overheated glue pot in a carpentry shop ignited. The fire quickly spread due to the wooden structures and dry conditions. It caused an estimated $20 million in damages equivalent to about $678 million in 2023 dollars.

After the fire the city was rebuilt, this time using bricks and the Butler Hotel was part of that effort.

As fate would have it, Ferdinand had sent for Emma to come to Seattle. While traveling from Germany, the fire struck and she arrived four days afterward on June 10, the city still smoldering.

The fire had destroyed 29 blocks of buildings, four wharves and more.

A wedding treasure Emma gave to Ferdinand was a scorched, blue vase she discovered amid the embers, literally still warm. She had to carry her gift to her husband from the ashes on a stick. It stood for years in their family home.

The Schmitz family had begun under very humble circumstances.

Living at first in tents, they moved into a home near 3rd and Madison Street. This is where Dietrich their first child was born in 1890. Henry came along 2 years later. The family moved to a larger home at 12th and Pike on Capitol Hill where daughter Emma was born in 1894. Ferdinand acquired several tracts of land in the Alki area of West Seattle between 1900 and 1905 comprising more than 120 acres including what was called Spring Hill and an area that would later became Schmitz Park.

In 1896 Ferdinand’s brother, Karl had passed away in Duisburg, Germany and a year later so did Karl’s wife, orphaning six children. Emma sent for the six and Ferdinand and Emma took all of them under their wing, housing four of them until maturity.

In the summer the family would travel to West Seattle via the well known Mosquito fleet of vessels that would dock at Carroll Street (the current site of Weather Watch Park on Beach Drive SW) and camp out and picnic near there.

They built a small cabin there in circa 1903 north of Jacobsen Road. That is where Ferdinand Jr. was born as the first non-native American baby south of Alki Point.

By 1905 they had built their larger 17-room German style home on Beach Drive. The family piped in water from hillside streams, kept at least one horse, a cow, guinea hens and peacocks, and stocked trout in a pond. They maintained gardens and a small fruit orchard.

Ferdinand Sr. was the first American to greet the Japanese on August 31 1896 when the first ship from that nation to arrive in Seattle the Miike Maru sailed into Elliott Bay. They were greeted with a 21 gun salute and a crowd of boats excited about their arrival.

He formed a great friendship with the ship’s crew and an appreciation for their culture and in later sailings, the Japanese government gifted him 75 cherry trees, white, rose and pale pink. Some of those trees, now famous for their spring blossoms, are still on the University of Washington campus.

Ferdinand Sr.'s civic contributions included advocating for the construction of the original Spokane Street Bridge over the Duwamish River. That came about after Ferdinand was coming into Seattle on a ferry from West Seattle to Seattle. The ferry lurched and a team of horses on board fell into his car, injuring his leg which led to him demanding a bridge be built to the community.

The family’s influence has been honored with the naming of the school just adjacent to the park, Schmitz Park Elementary, officially named in 1954.

Westside Seattle recently interviewed Ferdinand Jr.’s daughters, the granddaughters of the couple they called “Fafa” and “Mutter” Patricia “Patsy” Schmitz Carpenter and Nancy Schmitz Wilson. They shared memories of a man and the family that would have a profound impact on history of Seattle.

_____________________________________________

To learn more about the fascinating history of the Schmitz family by one of its members Gayle Schmitz Fulton click here

____________________________________________________

CLICK HERE TO WATCH THE FULL VIDEO INTERVIEW WITH THE SCHMITZ TWINS

Nancy Ann was born seven minutes before her twin sister, Patricia Ann. Both have vivid memories of their childhoods, especially of time spent at their grandparents' grand West Seattle home.

"We were very shy girls, loved to sew, garden and knit and loved being home with our family," Patsy said.

“I loved going to West Seattle,” Nancy said. “We usually generally went every weekend. Mainly on a Sunday to see ‘Mutter and Fafa’. I played with all my cousins that lived there. And it was wonderful. We would enjoy the beautiful garden and the little pond with an island with a bridge going across it. It was just a charming experience to have that German style of a home. Very strange with parlors, one for sewing and one for dancing where you had to wind up the Victrola by hand to have the music.”

Patsy recalled, “I remember Mutter and Fafa in the dining room. A huge, huge oval table and on one end of the house were leaded windows. At the far end of the house was a bench and it had nice cushion seating on it. Outside that window was a beautiful pond where the water came down and there were fish."

Family meals at Sans Souci were grand affairs, with "fabulous roast beef, and sauerkraut," and Emma's "wonderful zeppelin beans" taking center stage. These beans, brought from Germany by Emma, held a special place in their hearts, as did her "honey sugar cookies" – crunchy, chewy treats stored on the highest shelf to keep the grandchildren at bay.

The sisters say that the home was full of unique, charming features.

"Patsy said "To go through that house you had to pull a string in order to turn on a light to get to where you were going."

Nancy said, "There were no light switches. The telephone was on the wall and being little children, we were stacked up on many boxes to speak to a speaker and we would call Germany during the Second World War. And I remember we were constantly saying 'OVER' and it was quite a unique situation."

The home's old-fashioned nature was part of its charm, Patsy said.

"What was really fabulous about Mutter and Fafa’s house is that It was so old fashioned," she said. "I mean everything was reaching for a string. And our parents home in Mount Baker was quite a different type of residence. And so, we’d go there at least three to four days of the week to see those grandparents.

The twins attended the University of Washington, while Dr. Henry Schmitz their uncle, was President of the UW. Their father oversaw World War II production of tanks, jeeps and other military vehicles at Pacific Car and Foundry and later worked at Kenworth Motors. He then purchased Berger Engineering which made equipment for logging and oversaw its growth and expansion. Later, he purchased a chunk of property above Beach Drive in West Seattle and developed a large residential area called Schmitz Estates.

"I’m so grateful I had that experience that I wish a lot of people had in their life because I think it’s very telling that you don’t need a lot to to be happy. My grandmother although stern, was a happy person. She loved her garden. And the garden was magnificent."

The garden and home was a source of great joy for the family, the sisters recalled, and it was full of interesting and unexpected items.

“I was very impressed they had a piano and it impressed me that they had a small vase up on the top of the piano of cotton and they grew that cotton in their garden. They had every imaginable vegetable that you could think of growing that you wouldn’t think would grow in the northwest. They had chickens. It was just well beyond measure. They had a different world. You came down the hillside from their home, down into the garden and into row after row of berries. Second cousin Gayle and Nancy and I loved picking those berries, and we generally had Cousin Alan (the son of Dietrich) with us to pick berries."

“There were loganberries, raspberries, and then there were the peas. Now, we were told to pick peas. But we ate more than we picked, and Aunt Emmy got extremely upset about that," Patsy added.

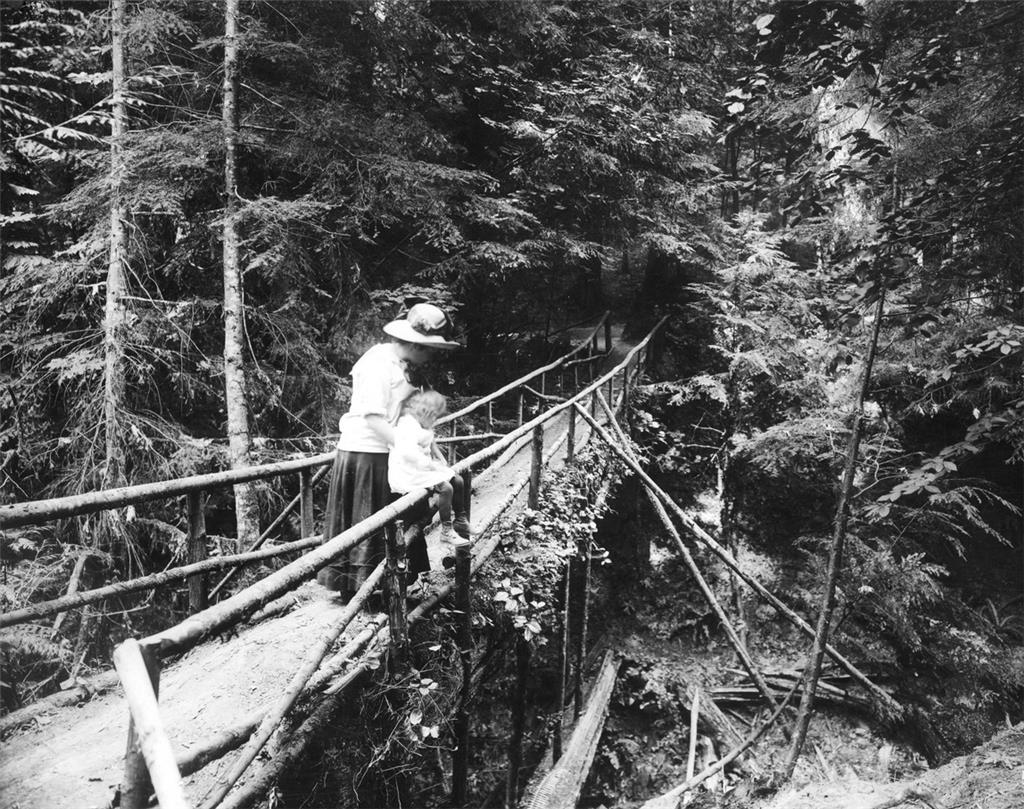

In 1908 Ferdinand and Emma donated 35 acres of land to the city with the condition that it never be logged, That land became Schmitz Preserve Park, one of the last stands of old growth forest in Seattle. Trails are allowed but no other cutting of trees or development has been permitted. As a result, the forest continues to thrive, and is largely untrampled and undisturbed. Additions to the park were purchased between 1909 and 1958, growing the park to a full 53.1 acres.

The park and its creek are now the focus of effort called Schmitz Park Creek Restore, whose aim is to raise more than $50 million to daylight the creek (routed years ago into a culvert due to neighborhood flooding), restore the salmon run, gone for many decades, and create structures on and near Alki Beach that will highlight the park, the creek and their history. They aim to pursue the creation of a cove and delta on Alki Beach near where the waters of Schmitz Park Creek originally met Puget Sound.

See our coverage about this here.

Ferdinand also served as Parks Commissioner from 1908 to 1914 and as a member of the Seattle City Council.

He became a banker, a partner in Hamm-Schmitz Realty Co., and the Rathskellar Co.

The twins recall that their grandparents would sit in a small alcove like room near the front of the house, Fafa in his Morris chair and Mutter across from him. Appropriately, a Grandfather clock in that alcove would chime on the hour.

The clock survives to this day on the first floor of the University of Washington (UW) Administration building, Schmitz Hall, named for their uncle Henry, UW President from 1952 to 1958.

The twins upbringing was very different than their grandparents. They lived in Shelton Washington until they were two, and then moved to Seattle settling in the Mount Baker neighborhood when they were young girls.

The twins and cousins would play pool upstairs in a large billiards room at San Souci, whose walls were adorned with posters and animal heads the product of Ferdinand’s hunting exploits.

Ferdinand Schmitz died in 1942. Emma then later donated 17 more acres to the city along Beach Drive SW including the land on which San Souci stood for a stunning view of the Olympic Mountains known now as the Emma Schmitz Memorial Overlook and Me Kwa Mooks Park. The area is also a marine preserve.

Their family home was torn down in 1967.

Ferdinand Jr who later would marry Margaret Duncan had a child, Ferdinand Schmitz III and then twin girls.

Both sisters have memories of visiting Schmitz Preserve Park with dates in their early 20’s. Patsy said, “We drove down when you could drive down and it was as I recall, a big circle for a parking area. And just soaring green trees. It was just absolutely gorgeous.”

Nancy said, “I think when I went It was more still open pathways. There were some trees knocked down and you had to climb over the logs, to get over the hump. But I think I did see it… We didn't go up all to the whole top of it, but we did enjoy seeing the park. I mean it was unique because there's very few places like it. If you were on the ferry, you could look over and see this very huge patch of evergreens, and I was always very proud to think that Fafa and Mutter thought enough about Seattleites that they would give land to the city.”

The sisters note that their father, the youngest of Ferdinand's Sr's children, recounted an anecdote that highlights ‘Fafa’s’ commitment to public welfare.

When a young Ferdinand jr. needed to use the restroom on a Saturday outing with his father, the only available option was a saloon. Determined to provide a more suitable alternative, Ferdinand Sr. used his position to secure property and personally oversaw the construction of the much-needed public facilities. The issue was a source of contention in the neighborhood based on opinions shared in the newspaper but he managed to get it built.

According to HistoryLink.org "This was indisputably the nation's most elaborately appointed underground rest room, with white-tiled walls, terrazzo floor, brass fixtures, and marble stalls. After the facility opened in September 1909, the toilets were flushed on an average of 8,000 times per day; 15,000 times on Sundays when saloons were closed. There were 16 stalls for men and nine for women. The toilets were closed after World War II."

Patsy emphasizes his quiet yet effective approach, stating, "Fafa was very civic-minded ... 'You do this for West Seattle or else.' So that's the way it went".

The city told him he would have to pay for it personally but they eventually paid him back, she explained.

Ferdinand Sr.'s civic contributions included advocating for the construction of the original Spokane Street Bridge over the Duwamish River. That came about after Ferdinand was coming into Seattle on a ferry from West Seattle to Seattle. The ferry lurched and a team of horses on board fell into his car, injuring his leg which led to him demanding a bridge be built to the community.

Growing up and getting married

Life changed for the sisters as they grew older and began to date and think about marriage.

They moved into a home at 55th and Genesee in West Seattle when they were just 22 and later moved to the Edgewater Apartments on Lake Washington when they were 28 and lived next door to their cousin, Mary Schmitz Hoff the daughter of their Uncle Henry and Aunt Melba. Their brother, "Ferdie" the 3rd and “Sis” were extremely close.

Nancy had met her future husband, Douglas Lyle Wilson, at a party at the Washington Athletic Club in 1959. In 1966, they married and a large family gathering followed.

Doug and Nancy were married in 1966.

Doug loved sailing and his Welsh Corgi dogs. The couple moved into the Edgewater Apartments, a complex popular among newlyweds, before Doug bought land for them to build a home.

"Doug had purchased this land that I’m on now," she said," And it had cost him…the total price of the land was $13,000. He had a gentleman move in and live with him in this little cottage house,” to help him build the larger home the couple had planned.

The couple worked to pay off the loan for the land, and used it to grow a variety of fruits and vegetables, much as Nancy's grandmother had done at San Souci.

" We had beautiful holly trees... wonderful vegetables and fruits. I think we gave more Italian prunes to the Seattle Food Bank than anyone could ever come up with by buying in a grocery store," Nancy recalled.

Doug lived to be 85 passing in 2015 and Nancy said they “enjoyed great times together.”

He left many memories of times of a "family of five" (referring to the twins and their husbands) spending time almost daily with Patsy's daughter Mary, with whom he shared a mutual love of dogs.

Patsy's path to love and marriage was a bit less conventional than Nancy's. She says that she fell in love with her husband, George, the day she met him.

He was a guest pastor and he delivered a powerful sermon whose words resonate with her to this day.

It was Holy Week and he said, "Imagine yourself at the foot of the cross,” Patsy explained.

"I fell in love with him in that Chapel that day," she said. "And the thing is it was just magical. It was absolutely magical.”

By contrast Nancy confirmed chuckling softly, "I dated my husband seven years" before they married.

After a chance meeting with George at Trinity Episcopal Church she would encounter him again at a house blessing

“They opened up the front door. Well, here stood this George. That’s interesting. He’s here," Patsy said.” After some punch and conversation “he turned to me, he said. 'You know, I’ve thought about you a lot'. I said, 'well, you have, that’s interesting.'

As the evening came to an end “he insisted to Nancy that he drive me home.” And Nancy said 'Oh no, no. Oh that won’t work out.' They had left the house a complete mess and would have been embarrassed to have guests. Demonstrating her love for her sister, while Patsy and George chatted, Nancy rushed home and cleaned the house from top to bottom. “ I went upstairs to my parents room and went to bed," Nancy said.

Patsy came upstairs around 2:00 am and said, "Nancy, I've met the man I'm going to marry."

The couple made plans to meet again, and Patsy said that after four dates -- one of which was their engagement -- they were married the following April.

Continuing in active Priesthood, non-stipendary, George pursued and retired in Private Trust banking.

Patsy was a homemaker and supported George's efforts.

A legacy to be proud of

The sisters say that they are proud to be part of the Schmitz family, and to carry on their family's legacy of community service and philanthropy.

"Very proud to be a part of it because every one of the four boys and the ones that we didn’t know very well from Germany were just wonderful Seattle citizens. They cared about people and they all worked, like my dad," said Nancy.

The sisters say that their father was a dedicated philanthropist, who worked hard to improve the lives of others. He helped to transform the Lighthouse for the Blind.

Today Patsy and Nancy are reunited living together again in Nancy’s home with Patsy’s husband George.

Reflecting on their lives, the sisters lament the loss of the close-knit community they experienced in their youth. They express a sense of "tragedy" at the changes they have witnessed in Seattle, noting that the city feels less personal and familiar than it once did.

But for Patsy and Nancy, the name Schmitz represents a commitment to community, family, and hard work -- values that they have strived to embody in their own lives.

They are pleased to see the renewed attention being paid to the park that bears their name. “I’ve read all that is trying to be accomplished there… and I think it's just phenomenal that such an undertaking would be pursued,” said Patsy, “Couldn't be a finer ending at 90 years old.”

"Very proud to be a part of protecting the Park because every one of the four boys, and the ones that we didn’t know very well from Germany, were just wonderful Seattle citizens. They cared about people and they all worked, like my dad," said Nancy.

Their stories, filled with warmth, humor, and a deep appreciation for their family and community, serve as a reminder of the enduring power of human connection and the importance of giving back to the places we call home.

___________________________________