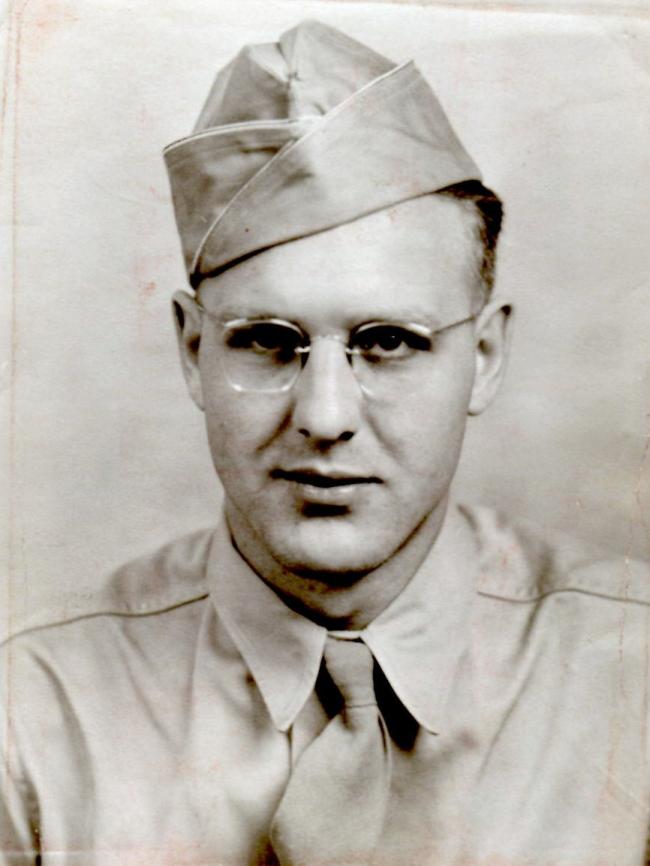

An Untold Life: John Nitkey

Sun, 09/22/2013

By Maggie Nicholson

As a boy, John Nitkey learned to swim the clear waters of C’oeur D’Alene Lake. The sun was amber honey, sticking to the air. John waded in to his skinny shoulders, his legs merging with blue. He was the only swimmer in the family. His mother Louise, father Andrew and sisters Mary and Evelyn, never learned. John lived with his sisters and parents in a small log cabin in Harrison, Idaho. Andrew built the cabin by hand, out of trees he cut down on their land. The cabin squatted on a 160-acre plot. The land was impenetrable: thick with quiet pine trees whose branches were taut and crisp and filled with shuffling forest birds. Andrew and Louise were given the homestead for free, on the condition that they work it.

Before moving into the cabin, the family had lived with Andrew’s brother in a house in Lane, Washington. The house burned down after pitch from the wood caught the residence on fire.

Andrew used mud to secure the log cabin together. When the first rains came, they swept through and destroyed the foundation. Andrew re-built, this time using cement-like adhesive. The cabin consisted of three rooms: a bedroom, kitchen, and living room. John slept in the bedroom with his parents. In the kitchen, a large double bed was propped up against splintering logs. Mary and Evelyn shared the bed there. There was no running water, no indoor plumbing, and light was fostered only by the insect-like oil lamps, buzzing and licking the walls with shadows.

Andrew turned the land into a dairy farm and timber yard. John helped, leading cows across the dark grassy pastures. At night, there was only the gliding line of moonlight across wild fields. He helped timber trees, chopping and selling lumber with his dad during the Great Depression. John dug an oil well by hand and made a makeshift gas pump half a block from the house. When someone drove up to the well, he would run down to pump gas and collect their money.

He took the bus to school, and walked home from afternoon sports. From basketball practice in town back through the lightless dirt road to the cabin was a long trek. In childhood, he didn’t know how long. As a man, visiting the farm with his wife, he calculated the distance. It was four miles. “Hell,” he said. “No wonder it felt so long!”

Growing up, John had one goal: getting off the farm. His son Larry recalls a country drive with his father. Larry was asking sporadic questions about farmers in the distance: reasoning behind certain machinery, names of ambiguous structures. John kept replying that he didn’t know.

“How is it you don’t know anything about farming?” asked Larry.

“The only thing I wanted to know,” said John. “Was how to get off the farm.”

When John got old enough, he packed his bags and headed to school in Spokane. He didn’t have enough money for campus housing. He lived out of a cheap room at the Arlington Hotel. Early in the morning, he delivered newspapers. He didn’t borrow a penny from anyone, and took out no loans. In the summers, he returned to the farm in Idaho to chop wood and sell lumber. When he graduated, he had already finished paying for his entire degree.

After finishing school, he met a nursing student named Frances. John was set up on a blind date with Frances’ roommate. Last minute, the roommate learned she had work, and convinced Frances to go on the date in her place. John and Frances fell in love. Years later, Frances introduced John to the girl he was supposed to have met that night. They were introduced in Nantucket. Seagulls pawed at the wet brown sand. He didn’t like her, he told Frances, and squeezed her hand. John and Frances married in Spokane in October of 1943. Three months later, John went to war.

He couldn’t have been drafted, since he was legally blind in one eye, but had registered himself for service before meeting Frances. They kissed goodbye and John left for Belgium.

In August of 1945, John boarded for the first time a ship headed for combat. The massive boat careened over dark water. The compass was set for the Pacific. Stars confirmed the direction. Oil smoke furrowed into the night sky.

Halfway there, the war ended. The men swallowed the lumps in their throats and the ship turned back around.

When John came home, he and Frances moved into the first home, a rental on Alki Ave. The first home they bought was in White Center, and the second in Arbor Heights. After working for a national accounting firm, John opened his own firm above the Southgate roller rink in White Center. Later in life, he was involved in building and owned many properties. John and Frances moved into the Arbor Heights house with three kids and moved out with five. They had six in their time together. John made breakfast in the morning and saw the kids off to school. They were never allowed to walk; he insisted on driving them. It was a pre-disposition carried from his childhood. John worked early in the morning through 3:30 in the afternoon. Frances was working as a nurse from four in the afternoon through midnight. They met in the driveway. John pulled in as Frances pulled out.

John was a godly man and attended church regularly. He met AJ Mulally at Holy Family. The two became best friends and business partners. They died within days of each other: John on March 15th of 2012 and AJ two days later.

John was a kind landlord. The family has a folder filled with grateful letters and notes from his tenants. Frances recalls a man cleaning the blinds in her apartment on Alki. He turned and asked if her husband was John Nitkey. Frances said he was. The man smiled, shook his head, and said he had lived in one of John’s properties years ago. ‘He couldn’t have been beat,” said the man.

John loved to read newspapers and often went to the library to sit and read the Wall Street Journal. As a boy, he did a lot of reading on the farm.

He moved his mother over from Idaho after his father died, so that she could be close to him and his sisters in Washington. John chose a house right next to a church for her, so she could walk to service there and also to a nearby farmer’s market for groceries.

In 1966, John drove his family to a reunion in Montana. They crammed seven people and a dog into a six-passenger car. On the way, they got a flat tire. John got out, put on the spare, and continued on, only to get another flat. He pushed the car to a serendipitously close gas station and had it patched. Then, impossibly: a third flat. They rolled the car to the side of the road. Nearby was a farm. Everyone slept in the car that night, their feet curled up under them: the dog passing gas and Grandma Louise nervously poking her head up to survey the land for bears. In the morning, they hitched a ride from a traveling pick-up truck, piling into the back. The truck pulled up to the reunion and all seven hopped out, stretching their limbs and laughing.

As a grown man, John loved visiting his parents’ farm in Idaho. He brought Frances with him, and together they walked every inch of the land, splitting the distance between childhood and manhood, the air as fresh and new as it always had been.