An Untold Life: Arlene Wade

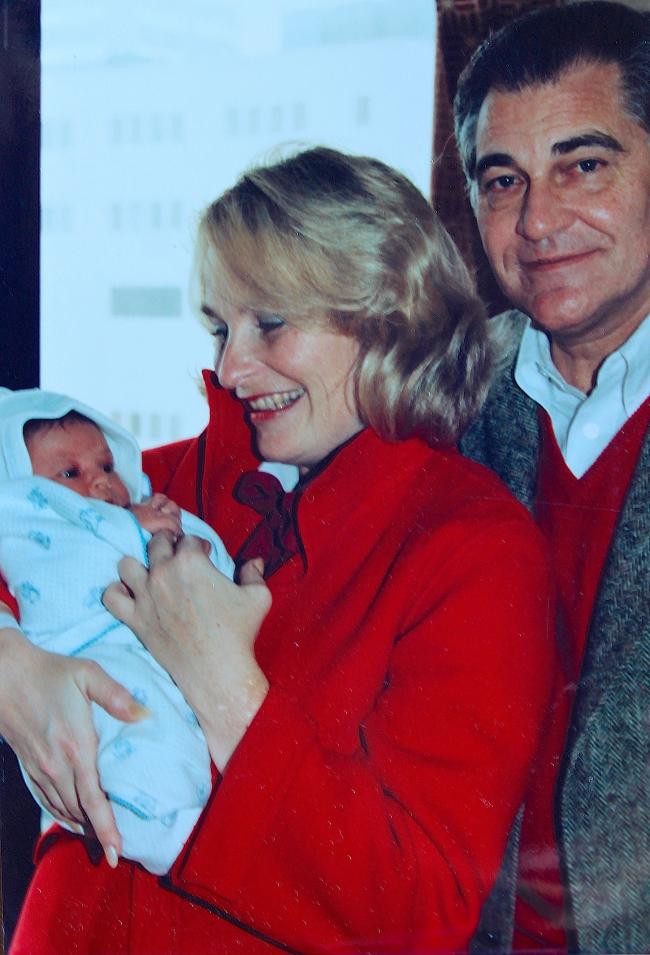

‘Arlene Wade, George and Brady, 1983.’

Fri, 05/10/2013

By Maggie Nicholson

An old compass, corroded at the edges, lies on the dashboard of my car. The arrow spins quickly, like arms lurching outward, as the car navigates bends. The road is unfamiliar, and on one side water moves as one morose glob, slurping magnetically at little rocks. I am leaving an interview with George Wade on his late wife Arlene, and am left with his words. I watch the radial turns of the compass hands: unexpected, rapid and brief. I had asked how Arlene Wade became involved with the Duwamish: an Indian tribe she grew to help and love profoundly.

“Life doesn’t always happen A to B to C to D,” said George. “Sometimes you jump from A to H, then make a zig to Z, only to come back to B after that, without even trying to.”

Arlene Wade’s life will be remembered for its positive influences. Her paths and direction, whether carried on the wind or imprinted by fate, led her to greatness, success and charity in countless fields.

Arlene was born in the green pastures of Port Orchard. Her father Ray Hinderlie was principal of South Kitsap High School. Her mother Irene worked for the government during World War II. She had two brothers named Richard and Sanford. Richard became a financier for the state of Colorado, and Sanford became a chaired Professor of Music at Loyola College in New Orleans. As a young girl, in freshly ironed dresses, Arlene played the organ for her church. She remained close with eight of her childhood friends. As women, her friends brought flowers and foods to her home, helping her decorate and clean. Arlene and one of her close girlfriends, volunteered at elderly homes together, singing and visiting with residents.

Arlene was named Miss Kitsap and then Miss Seafair, in 1963. It was an important year to be crowned: festivities abounded during the World Fair in Seattle. The title designated a strong combination of beauty, intellect and talent. Arlene demonstrated her musical abilities; she also won the bathing suit contest. Bob Hope, legendary movie star, shared a big kiss on the cheek with her. Elvis Presley had left footprints behind on the crowded streets. Only a hand was able to deter the heavy sun: shielding the light and breaking it into fragments. The Seattle Space Needle rose up from the ground like a plant. The world felt new.

Arlene went to the University of Washington for her undergraduate degree. In college, she lived with Gamma Phi Beta sisters in a shared house. The sisters later told George they felt Arlene was their “number one girl.” At nights, for fun, Arlene was the lead singer for a local band. They performed occasionally at a small venue in Queen Anne.

Following her undergraduate degree, Arlene got her MSW at the University of Washington, achieving the degree with straight A’s. She then completed a three-year adult therapy program at the Seattle Psychoanalytic Institute.

Arlene met George at the University of Washington while she was working toward her MSW. George had an undergraduate degree from Yale and was moving toward his Ph.D.

George was introduced to Arlene in 1969 by Arlene’s first husband, Tom Jackson. Tom was George’s insurance agent. “You’ve got to meet my wife,” he said. Tom was deeply proud of Arlene. After Arlene and George’s first marriages ended, the two fell madly in love with one another. They were married in 1977, at the Seattle Tennis Club.

A provost from Pacific Lutheran University acted as priest for the wedding. The couple traveled to every continent in the world. Arlene, who studied photography under the direction of Josef Scaylea, never detached the camera from her neck. She took photos of everything. “Hold it there, hold it there,” she’d say to George, panning her hand left or right. For every photograph of herself, there were hundreds of George.

Arlene and George visited Peru, traveling down a tributary of the Amazon River late at night. The sky and river were black. Starlight peered out meekly through cloud cover. A singing chorus of insects weighed down the thick air like perfume. Interjections of small splashes disrupted the placid river. “Alligators,” said their tour guide, when questioned. Arlene and George slept at a camp in the middle of the rainforest that night. Their shared bed was veiled by pale netting. It would keep the snakes out.

The couple traveled to their second home in France for many years, on visits. On September 11th of 2001, half of the small village they resided in came in waves to set flowers on the front porch of their little farmhouse.

Arlene and George, in their time together, entertained three kings and two queens, including King Olav of Norway. One royal couple so adored Arlene that they insisted on boarding the private ship she and George were on, in order to eat breakfast with her once more.

In 1983, they gave birth to their son, Brady. Arlene retired from her work as an adult psychotherapist in order to raise him. Brady was co-captain and linebacker on his football team as well as the MVP for his baseball team. He became an exceptional violinist, even performing in the All Northwest competition. Arlene accompanied him at the event, on piano.

The family moved to Normandy Park in order to be closer to Arlene’s parents, as they grew older. They bought a home with the most monumental library George had ever seen. The owner of the home was a widow, who told him George he reminded her of her deceased husband. She gave them a deal on the house on one condition. George was to take her out on her anniversary each year, to the restaurant she had often gone to eat with her late husband.

Arlene saw citizens without their races. She loved everyone, irrespective of nationality. She became involved in a cause she passionately believed in: memorializing the birthplace of Seattle. The first settlers of Seattle landed on Alki Beach in 1851. They received vital assistance from the Duwamish tribe. Without their help, the settlers would have starved. Seattle was named in honor of Duwamish Indian Chief Sealth.

Arlene and George helped the Duwamish tribe secure sacred ancestral land, which had, for years, been an argument over fishing rights along the river. The tribe used the land to construct a Longhouse. The Longhouse is not extravagant or ornate. The wood is handpicked; the floor is solid and magnificent. On May 4th of 2013, the tribe gathered to celebrate Arlene. They bestowed upon her a tribal name: ‘Wild Eagle Woman.’ They did a healing dance for George. The daughter of the Chief rose from the ground, tears welling in her eyes, to speak in memory of Arlene. Peter Steinbrueck, mayoral candidate for Seattle, also spoke at the ceremony, fondly remembering Arlene and her important advocacy for the Duwamish.

At one point during the ceremony, the females were asked to dance together. Every single woman in the Longhouse rose to their sturdy feet and spun in tight knots across the glowing wooden floor. Native American women and Caucasian women with silver hair spun in synchronicity, their arms sweeping through the air like dandelions in the wind.

Arlene was deeply spiritual. “She wasn’t the type to yell Hallelujah and sock it to you,” said George. “But she believed in God.” Arlene lived what Christ taught, with compassion and morality that came to her as water comes downstream: with little resistance, and as natural as gravity. Toward the end of her life, she and George prayed together every night.

The only thing that ever got her downhearted was the thought of weighing down another person. She was a strong woman, who cared so much for others, that their wellbeing took precedent, even during her cancer.

The couple shared one bed throughout their marriage, despite the intensification of Arlene’s illness. One night, wrapped in each other’s arms, George came to realize how much Arlene had accomplished silently. So many people were calling to let her know how important she was to them. There were people calling that she had never even discussed with George. “I don’t want to bullshit you,” he told her. “But I need you to know how impressed I am by you.”

Arlene didn’t need to acknowledge aloud the good work she was doing. She didn’t revel in it. Her compass, whose hands surely swiveled as paths changed, led her where her heart allowed it to lead. A compass ruled by a heart like that could not ever steer a person wrong.