Is Seattle protecting our waterway?

Seattle Public Utilities and King County are building underground stormwater and sewer storage.

Thu, 03/09/2017

By Brando Reece-Gomez

Masters of Landscape Architecture Candidate

University of Washington

As we all are aware, on February 9th, the West Point Treatment Plant flooded, and as a result, operations shut down, leading to $25 million of repair damage. An estimated amount of 300 million gallons of untreated sewage and stormwater was discharged in to the Puget Sound. This event highlights the fact that Seattle does not have control over our combined sewage and stormwater systems. 300 million gallons may sound like a lot, and it most definitely is an incredible amount of effluent, but relative to the amount of untreated effluent being discharged into our major water ways each year, (Puget Sound, Lake Union, Duwamish River, Ship Canal, and Lake Washington), hundreds of millions of gallons is not uncommon. In 2015, The City of Seattle and King County finalized a plan titled The Plan to Protect Seattle’s Waterways, which aims to reduce polluted sewage and stormwater from entering our major water bodies through the city’s 86 combined sewage overflow (CSO) outfall locations. This plan will invest major time and money for antiquated and costly approaches, and significantly underestimates the efficacy of performative wetlands and green infrastructure. We live in the 21st century, yet the city is failing to employ 21st century solutions.

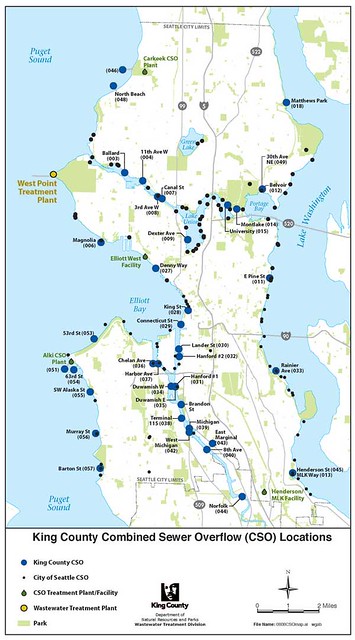

Right now, the Washington State Department of Ecology authorizes the City of Seattle to discharge combined sewer and stormwater at 86 CSO outfall locations. During a heavy rain, Seattle’s combined sewage infrastructure becomes so full that relief comes in the form of secondary piping, which leads directly to CSO outfalls and directly in to our water ways. The figure below shows the locations of these outfalls.

Locations of these outfalls. Courtesy of City of Seattle.

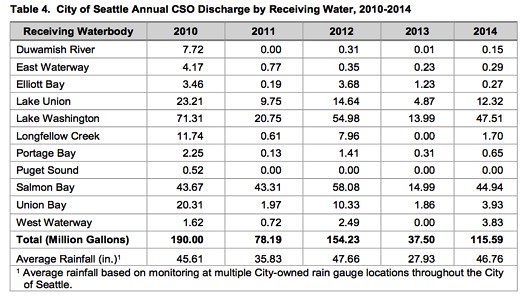

These 86 CSO outfall locations account for the discharge of tens to hundreds of millions of untreated sewage and stormwater each year. The figure below shows the amounts of discharge recorded from 2010-2014.

Amounts of discharge recorded from 2010-2014.

Why is stormwater runoff a problem? On a rainy day, what you see is water flowing down our city streets, but what you do not see are toxic chemicals, fossil fuels, plastics, metals, pesticides, and bacteria. Here in the pacific northwest it is a problem that influences the health of our families, the region’s biodiversity, and more acutely our salmon. A study from the Nature Conservancy and Washington State University, found that 60-80 percent of fish that return to our waterways to spawn are dying from urban pollution. A link to a video is posted below. A normal rate of pre-spawn mortality is closer to 1 percent of the population that may die before they get a chance to spawn. Even the ones that do survive, have ingested toxic waste that can cause swelling of the heart, an inability to swim, and eventually death. The study also found that using a simple blend of sand and compost can successfully filter urban runoff, and salmon that were subjected to this filtered water lived. Stormwater runoff not only creates a human health risk, but damages the health of the receiving water bodies. Our responsibility to ecosystems means we should have the capacity to deal with our own waste rather than expecting the rest of the ecosystem to do it for us.

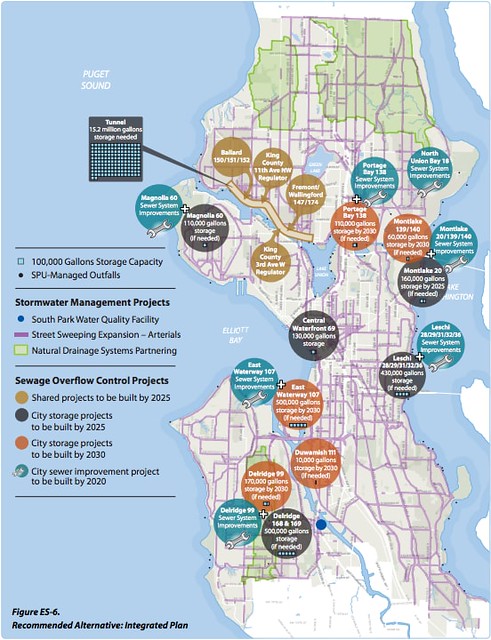

Capacity and flow management are key to successful wastewater management. We need a plan to eliminate discharge completely, reducing pollution is not a solution to eliminating pollution. The Plan to Protect Seattle’s Waterways will begin construction on a series of underground storage projects, widespread street sweeping, and natural drainage systems. The map below shows a detailed map of the projects proposed to be completed as late as 2025.

Detailed map of the projects proposed to be completed as late as 2025. Courtesy of the City of Seattle.

One of the proposed storage projects is a 2.7-mile underground tunnel, located through Fremont and Ballard. During a heavy rain, instead of wastewater being discharged in to salmon bay, the storage tunnel will hold up to 15 million gallons of sewage and stormwater, and on a drier day, the holdings will be pumped to West Point Treatment Plant. This project is not expected to finish until 2023, and while the city claims it will do little to disrupt adjacent communities, I speculate increased traffic due to construction and further pollution from construction will surely be an issue.

This is a major investment project for the city and county, yet it is disappointing to see their lack of vision and awareness of the positive possibilities major investments like this can have. Why is there not coordination with the Burke Gillman Trail extension, and Burke Gillman trail altogether? Constructed wetlands and streetscapes with water retention capabilities can collect, filter, and treat sewage and stormwater successfully. These green technologies are less expensive to install, are arguably just as effective as underground storage basins, and provide valuable greenspace that residents of a growing city want! Why is our city investing in antiquated, underground systems that are difficult and expensive to construct, manage, and do not provide any social benefit? When you take a strong force such as utility and necessity, and you combine it with positive social and environmental impact, the result is something powerful. We are missing out on an opportunity to take control of our sewage and stormwater pollution, eliminate it, and create a city that fosters an appreciation for this natural environment which we share. They underestimate the efficacy of green infrastructure as a means to manage our wastewater pollution, and leverage the necessity of dealing with this pollution crisis, as a way to build beautiful and functional transportation networks and public space.