City is stepping up to address homelessness in West Seattle; but many residents remain distrustful

The city held an open house on Dec. 8, discussing the new homelessness encampment site on Myers Way S. Many participants expressed skepticism and distrust.

Fri, 12/09/2016

By Gwen Davis

Homelessness is a crisis in Seattle. Fortunately, the city is responding.

In September, the city released a plan to transform the current homeless service delivery system, so that people who are experiencing homeless will have more access to longer-term solutions. The city will invest over $50 million in shelter and services.

However, transforming the system will take time. In the interim, Mayor Ed Murray convened a task force to provide recommendations on how the city can best respond to individuals who are in crisis now.

On December 1 of this year, the city announced three new sanctioned encampment locations, one of which will be located on 9701 Myers Way S. with capacity to serve 60-70 people. The encampment will be permitted for 12 months with an option to renew for an additional year. The city is in discussion with potential operators for the Myers Way site.

The site was chosen, out of dozens of potential sites, for several reasons. First, it is located more than one mile away from other encampments. Also, it is in a non-residential zone, it's close to transit and has a lot size of more than 5,000 square feet.

The encampment will open in January.

The site is not low-barrier, meaning that residents need to be clean and sober, and cannot bring partners or pets. (By contrast, one of the other new sites on 86th and Nesbit will be low-barrier.)

The Seattle Police Department (SPD) has determined that such encampments do not uptick crime. The neighborhoods surrounding the current encampments in Ballard and Interlay have not experienced an increase in criminal activity.

However, SPD will increase patrols in the immediate areas. The new sites, including Myers Way, will have regularly scheduled garbage pickup. Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) will step up efforts to pick up garbage quickly, and has initiated a program to pick up needles within 24 hours of notification.

Each encampment is also required to have a community advisory council, whose members will include the operator, community members and encampment residents. The meetings will be monthly and open to the public. The councils will trouble-shoot problems and make issues transparent to the greater community.

But the city does not feel that encampments are a long-term solution. These encampments are part of the interim plan, as the city implements its "Pathways Home" to adequately address the homelessness crisis.

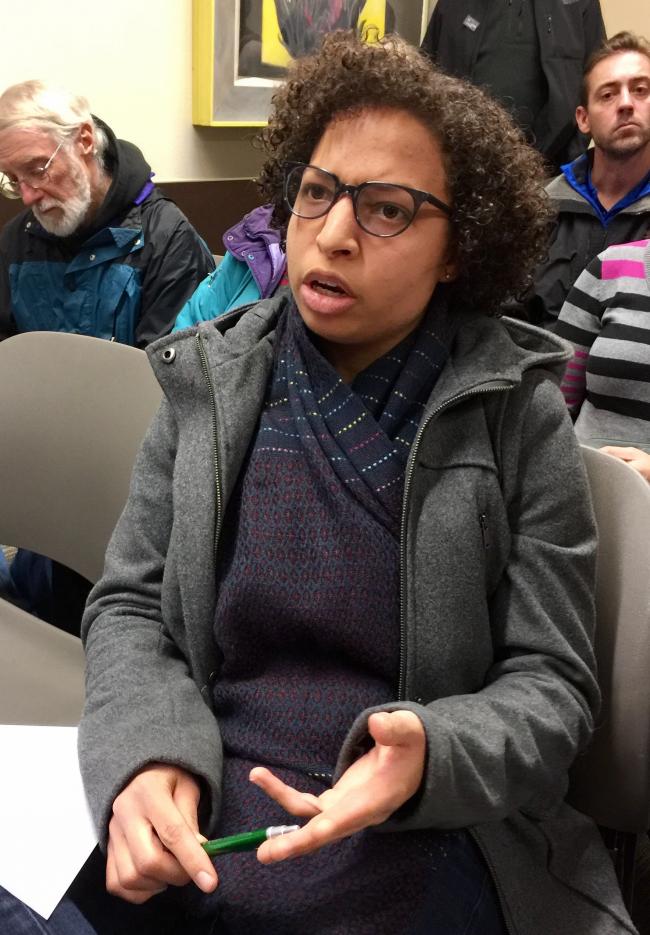

On Dec. 8 the city hosted an open house regarding the Myers Way encampment. George Scarola, the city’s director of homelessness facilitated the meeting. Around 50 people showed up.

However, comments were heated. Many participants expressed distrust and resentment of the city’s plans.

“Highland Park hosted Nicklesville for several years,” one participant said. "You are asking us to step up and take this issue up again." The area is already dealing with low-performing schools and illegal dumping. “Also, by putting people in the middle of nowhere without any services, you’re doing more harm do their health.”

“The city is setting people up to fail,” the participant continued. “I’m someone who worked really hard to get out of homelessness. We need some infrastructure, and need the city to make a commitment to us and stop overlooking us.”

Another participant who lives in the area said: “I called the police twice today because of homelessness. I’ve spent over a thousand hours this year writing letters, calling the police — we feel terrorized.”

However, a couple participants expressed “hope” about the Myers Way encampment, and were glad the city was actively working on it.

One person said she is a survivor of a traumatic brain injury and PTSD.

“I am not my diagnosis, though,” she said. “I see hope. We can figure this out together. I know that this is hitting home for all of us.”

One of the city’s staffers made clear that the city will pay for a case manager, which is critical.

“The fact that we’re hiring a case manager is big,” she said. “This will open up a greater opportunity to get people in stable housing.”

She also pointed out that the city is paying for facility site, as well as all equipment.

Still, many participants felt skeptical.

One person commented that most of the areas that were looked at for encampments were places where residents generally have have less income, more children and where there are more immigrants. It’s unfair that wealthier, more white areas don’t receive encampments, like minority-populated neighborhoods do, he said.

But Scarola responded that while the south end has traditionally and disproportionally served more people who are homeless than other parts of Seattle, the city is asking other areas to take their fair share. Sand Point, one of the wealthier and whiter areas in the city also recently needed to accommodate homelessness services.

But emotions were strong.

“I’m telling you the situation is intolerable,” one participant said. “I want you to take action.”